-

Sylvhia.

User deleted

The Valley of Artisans : Deir el-Medina

Deir el-Medina is an ancient Egyptian village which was home to the artisans who worked on the tombs in the Valley of the Kings during the 18th to 20th dynasties of the New Kingdom period (ca. 1550–1080 BC)The settlement's ancient name was "Set Maat" (translated as "The Place of Truth"), and the workmen who lived there were called “Servants in the Place of Truth”. During the Christian era the temple of Hathor was converted into a Church from which the Arabic name Deir el-Medina ("the monastery of the town") is derived.

The site is located on the west bank of the Nile, across the river from modern-day Luxor. The village is laid out in a small natural amphitheatre, within easy walking distance of the Valley of the Kings to the north, funerary temples to the east and south-east, with the Valley of the Queens to the west. The village may have been built apart from the wider population in order to preserve secrecy in view of sensitive nature of the work carried out in the tombs.

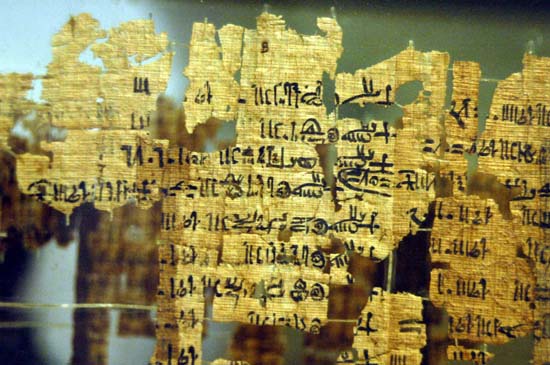

A significant find of papyri was made in the 1840s in the vicinity of the village and many objects were also found during the course of the 19th century. The archaeological site was first seriously excavated by Ernesto Schiaparelli between 1905–1909 which uncovered large amounts of ostraca (a piece of pottery (or stone), usually broken off from a vase or other earthenware vessel. In archaeology, ostraca may contain scratched-in words or other forms of writing which may give clues as to the time when the piece was in use).

At the time when the world's press was concentrating on Howard Carter's discovery of the Tomb of Tutankhamun in 1922 a team led by Bernard Bruyère began to excavate the site. This work has resulted in one of the most thoroughly documented accounts of community life in the ancient world that spans almost four hundred years. There is no comparable site in which the organisation, social interactions, working and living conditions of a community can be studied in such detail.The Village

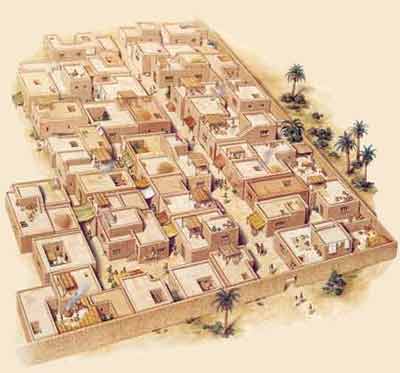

he first datable remains of the village belong to the reign of Thutmosis I (c. 1506–1493 BCE) with its final shape being formed during the Ramesside Period. At its peak, the community contained around sixty-eight houses spread over at total area of 5,600 m2 with a narrow road running the length of the village. The main road through the village may have been covered to shelter the villagers from the intense glare and heat of the sun. The size of the habitations varied, with an average floor space of 70 m2, but the same construction methods were used throughout the village.

Walls were made of mudbrick, built on top of stone foundations. Mud was applied to the walls which were then painted white on the external surfaces with some of the inner surfaces whitewashed up to a height of around one metre. A wooden front door might have carried the occupants name. Houses consisted of four to five rooms comprising an entrance, main room, two smaller rooms, kitchen with cellar and staircase leading to the roof. The full glare of the sun was avoided by situating the windows high up on the walls. The main room contained a mudbrick platform with steps which may have been used as a shrine or a birthing bed. Nearly all houses contained niches for statues and small altars. The tombs built by the community for their own use include small rock-cut chapels and substructures adorned with small pyramids.

Due to its location, the village is not thought to have provided a pleasant environment: the walled village takes up the shape of the narrow valley in which its situated, with the barren surrounding hillsides reflecting the desert sun and the hill of Gurnet Murai cutting off the north breeze as well as the view of the verdant river valley. The village was abandoned c. 1110–1080 BCE during the reign of Ramesses XI (whose tomb was the last of the royal tombs built in The Valley of the Kings) due to increasing threats of Libyan raids and the instability of civil war. The Ptolemies later built a temple to Hathor on the site of an ancient shrine dedicated to her.

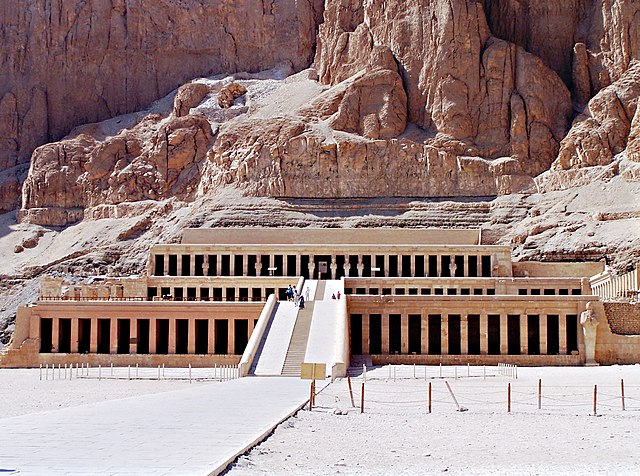

(Temple of Hathor)

The settlement was home to a mixed population of Egyptians, Nubians and Asiatics who were employed as labourers, (stone-cutters, plasterers, water-carriers), as well as those involved in the administration and decoration of the royal tombs and temples. The artisans and the village were organised into two groups, left and right gangs who worked on opposite sides of the tomb walls similar to a ship's crew, with a foreman for each who supervised the village and its work.

As the main well was thirty minutes walk from the village, carriers worked to keep the village regularly supplied with water. When working on the tombs the artisans stayed overnight in a camp overlooking the mortuary temple of Queen Hatshepsut (c. 1479–1458 BCE) that is still visible today. Surviving records indicate that the workers had cooked meals delivered to them from the village.

Based on analysis of income and prices, the workmen of the village would, in modern terms, be considered middle class. As salaried state employees they were paid in rations at up to three times the rate of a fieldhand, but unofficial second jobs were also widely practiced.[26] At great festivals such as the heb sed the workmen were issued with extra supplies of food and drink to allow a stylish celebration.

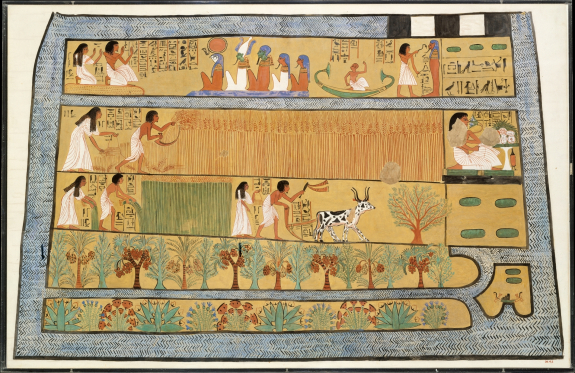

(image from Sennedjem's Tomb, an artisan of the Valley)

The working week was eight days followed by two days holiday, though the six days off a month could be supplemented frequently due to illness, family reasons and, as recorded by the scribe of the tomb, rowing with wife or having a hangover. Including the days given over to festivals, over one-third of the year was time-off for the villagers during the reign of Merneptah (c. 1213–1203 BCE).

During their days off the workmen could work on their own tombs, and since they were amongst the best craftsmen in Ancient Egypt who excavated and decorated royal tombs, their own tombs are considered to be some of the most beautiful on the west bank.

A large proportion of the community, including women, could at least read and possibly write.

The jobs of the workers would have been considered desirable and prized positions with the posts being inheritable.

The examples of love songs recovered show how friendship between the sexes was practised, as was social drinking by both men and women. Egyptian marriages amongst commoners were monogamous but little is known about the marriage or wedding arrangements from surviving records. It was not unusual for couples to have six or seven children with some recorded as having ten.

Separation, divorce and remarriage occurred. Merymaat is recorded as wanting a divorce on account of his mother in-law's behaviour. Girl slaves could become surrogate mothers in cases where the wife was infertile and in doing so raise their status and procure their freedom.

Women were supplied with servants by the government to assist with the grinding of the grain and laundry tasks.The wives of the workers cared for the children and baked the bread, a prime food source in these societies. The vast majority of women who had a particular religious status embedded in their names were married to foremen or scribes and could hold the titles of chantress or singer with official positions within local shrines or temples, perhaps even within the major temples of Thebes. Under Egyptian law they had property rights. They had title to their own wealth and a third of all marital goods. This would belong solely to the wife in case of divorce or death of the husband. If she died first it would go to her heirs, not to her spouse. Brewing of beer was normally supervised by the Mistress of the House, though the workmen considered the monitoring of the activity as a legitimate excuse for taking time off work.

The community could move freely in and out of the walled village but for security reasons only outsiders who had good work related reasons could enter the site.

Law and Order

The workers and their families were not slaves but free citizens with recourse to the justice system as required. In principle any Egyptian could petition the vizier and could demand a trial by his peers. The community had its own court of law made up of a foreman, deputies, craftsmen and a court scribe, and were authorised to deal with all civil and some criminal cases, typically relating to the non-payment of goods or services. The villagers represented themselves and cases could go on for several years, with one dispute involving the chief of police lasting eleven years.The local police, Medjay, were responsible for preserving law and order as well as controlling access to the tombs in the Valley of the Kings.

The people of Deir el-Medina often consulted with oracles about many aspects of their lives including justice. Questions could be put in writing or orally before the image of the god when carried by priests upon a litter. A positive response could have been made by a downward dip and a negative by a withdrawal of the litter.

Health Care

Like in other Egyptian communities, the workmen and inhabitants of Deir el-Medina received care for their health problems through medical treatment, prayer, and magic. Nevertheless, the records at Deir el-Medina indicates some level of division, as records from the village note both a “physician” who saw patients and prescribed treatments, and a “scorpion charmer” who was specialized in magical cures for scorpion bites.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Deir_el-Medina.

The Valley of Artisans : Deir el-Medina01 Luglio 2014 |